Fast trains to nowhere in Southeast Asia

Despite various schemes underway to upgrade decrepit railways, few are designed with a vision towards improving regional connectivity

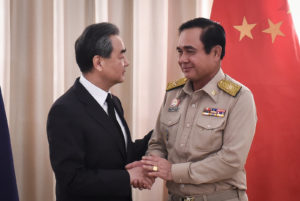

China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi urged Thailand on a July 24 visit to strengthen “cooperation in the construction of the China-Thai railway,” calling the kingdom “a very important partner” in China’s One Belt One Road initiative.

Yi did not make clear, at least in his press statement, where the cooperation needed to be strengthened, but better coordination between Thailand and its neighbors would be a good starting point.

Last month coup-installed Thai Prime Minister Prayut Chan-ocha used his extraordinary powers under Article 44 of the military’s interim constitution to push through the long-delayed China-Thai high-speed train project, sweeping aside certain legal obstacles such as Thai regulations barring Chinese engineers from working on the project without local licenses.

The project, which has been on government drawing boards since 2010, is still a far cry from securing a high-speed link between Thailand and China any time soon.

Under its current design the Sino-Thai high-speed rail will provide a 252.5-kilometer-long link between Bangkok and Nakhon Ratchasima, the largest city in northeastern Thailand. The project will be financed by Thailand, costing an estimated 179 billion baht (US$5.4 billion.)

The train’s top speed will be 250 kilometers per hour, averaging 180 kph, a slow pace for high-speed trains which can reach up to 380 kph elsewhere. Thailand, which has no experience with building high-speed railways, will use a Thai contractor to build the tracks while hiring Chinese experts to do the detailed design, construction consulting and engineering.

Exact details of the deal have not been publicly disclosed but observers anticipate Thailand will purchase Chinese trains and equipment for the rail.

Chinese engineers will apparently need to take crash courses in Thai engineering standards, local topography and the Thai language. Previous Chinese designs of the project have been submitted in the Chinese language, according to local reports.

There is an understanding that this first-phase project will lead to a second-phase high-speed connection between Nakhon Ratchasima and Nong Khai, on the border with Laos, to hook up with the Laos-China Railway Project which is currently under construction in Laos, and on to the southern Chinese city of Kunming.

Before proceeding with that expensive extension, Thai officials would be wise to research what their neighbors are doing.

On December 25, Laos officially started work on a 414-kilometer-long Laos-China Railway project linking its northern city of Boten, on the Lao-China border, to Vientiane, the Lao capital.

The project, which is being undertaken as a joint venture between the two governments (Laos 30%; China 70%) will cost an estimated US$6 billion, equivalent to almost half Laos’ gross domestic product (GDP) of US$13.7 billion in 2016.

The initial investment will be US$2.38 billion, of which Laos’ contribution is US$715 million, with US$250 million coming from the national budget and US$465 million from a loan from the Export-Import Bank of China at 2.3% interest.

It represents the largest infrastructure investment ever undertaken by nominally communist Laos, still ranked among the world’s least developed nations after recent years of fast growth.

Some economists wonder how the single-track, 1.435 mm standard gauge rail link will benefit the 6.8 million Lao population. The six Chinese contractors constructing the link plan (requiring 75 tunnels and 167 bridges) plan to use 30,000 Chinese laborers.

There are also questions about how the railway, which will travel at a top speed of 160 kph for passenger services and 120 kph for freight, will link up with Thailand and its deep-sea ports in Laem Chabang and Map Ta Phut on the Eastern Seaboard.

The Laos-China Railway should be completed in five years. Thailand has not even started on its Bangkok-Nakhon Ratchasima high-speed link or set a deadline for its completion, let alone the link to Laos.

Thailand is, however, moving ahead with plans to transform its single, one-meter gauge track in northeast Thailand in to a double-track, which would facilitate the transport of freight from the region to its deep-sea ports.

Work is already underway on building double tracks from Nakhon Ratchasima to Khon Kaen and southwards to Laem Chabang port. These projects should be completed in five years by 2022, but work on the Khon Kaen – Nong Khai connection hasn’t begun for the double-track project, not to mention any high-speed connection.

Thailand’s double-track plans were one reason negotiations fell apart between China and Thailand over their initially planned high-speed project as a joint venture. The original Sino-Thai railway was to provide a high-speed connection between Bangkok and Vientiane.

However, bilateral talks disintegrated last year when the Chinese side came to Thailand was moving ahead with a double-track one-meter gauge railway on their side of the border that would compete for passenger and freight business, according to a source familiar with the situation.

“After that the intention of the Chinese to invest in the project seemed to fade away,” said Sumet Ongkittikul, a transport and logistics expert at the Thailand Development Research Institute (TDRI) a Bangkok-based think tank.

Thailand has been following its own double-track plan without apparently consulting its northern neighbor Laos, which has meanwhile committed to a huge investment in a standard gauge train track that will have no connection to Thailand and the sea.

Trains on standard gauge (1.435 mm) tracks cannot shift on to one-meter gauge. “We are following the developments in Laos very little,” acknowledged Sumet. “Actually, we should have more cooperation between the two countries to have more benefits from these kinds of investments.”

Both Thailand and Laos are members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean), a regional grouping that is striving for greater economic integration under the Asean Economic Cooperation (AEC) trade pact.

Thailand is not alone in concentrating on its own domestic train system instead of regional connectivity. In Myanmar, investments are being made in upgrading the Yangon-Mandalay rail line, a crucial link for the country’s central plains to its main port.

In 2014, the country shelved indefinitely plans to have China build a US$20 billion high-speed train connection between western Rakhine State and Kunming, China.

In Cambodia, the Royal Railway Group has invested in sprucing up the Phnom Penh-Sihanoukville 264-kilometer-long rail connection, which is now offering a cheaper cargo transport alternative to Route 4. The railway also offers passenger services to Sihanoukville on weekends.

But plans to revive the 386-kilometer northern rail link between Phnom Penh and Poipet, on the Thai-Cambodian border, appear to be headed nowhere. One portion of the Poipet line is embedded in a cement sidewalk in front of a casino, an indication of how serious Cambodia is about reestablishing a rail link with Thailand.

Some observers blame Thailand for failing to take a stronger lead in assuring that domestic railway projects in the Cambodia-Laos-Myanmar-Vietnam region follow a long-term vision of enhancing connectivity.

“The problem now with Thailand is we have become more Thai-centric, especially with this government,” said Ruth Banomyong, a logistics and transport expert at Bangkok’s Thammasat University. “As a country, we need to have a clearly defined strategy as to how we want to help our neighbors.”

That Thai-centric trend, some suggest, might extend to Thailand’s neighbor to the north, China. “Even though they are saying they need to be linked to the One Belt One Road, the reality is that OBOR is not something that critical for Thailand,” Ruth said.

“It’s really more about China’s Middle Kingdom perspective on the world, but because of all the things China has done to support Thailand after the coup they feel they need to jump on this particular bandwagon.”

Source:http://www.atimes.com/article/fast-trains-nowhere-southeast-asia/