Is Thailand’s land bridge plan connecting the Gulf of Thailand and the Andaman Sea just a pipe dream?

Cargo vessels loaded with containers are on both sides of the sea, clearly representing the South China Sea in the Gulf of Thailand and the Andaman Sea. In between are a train and truck that connect the two coasts.

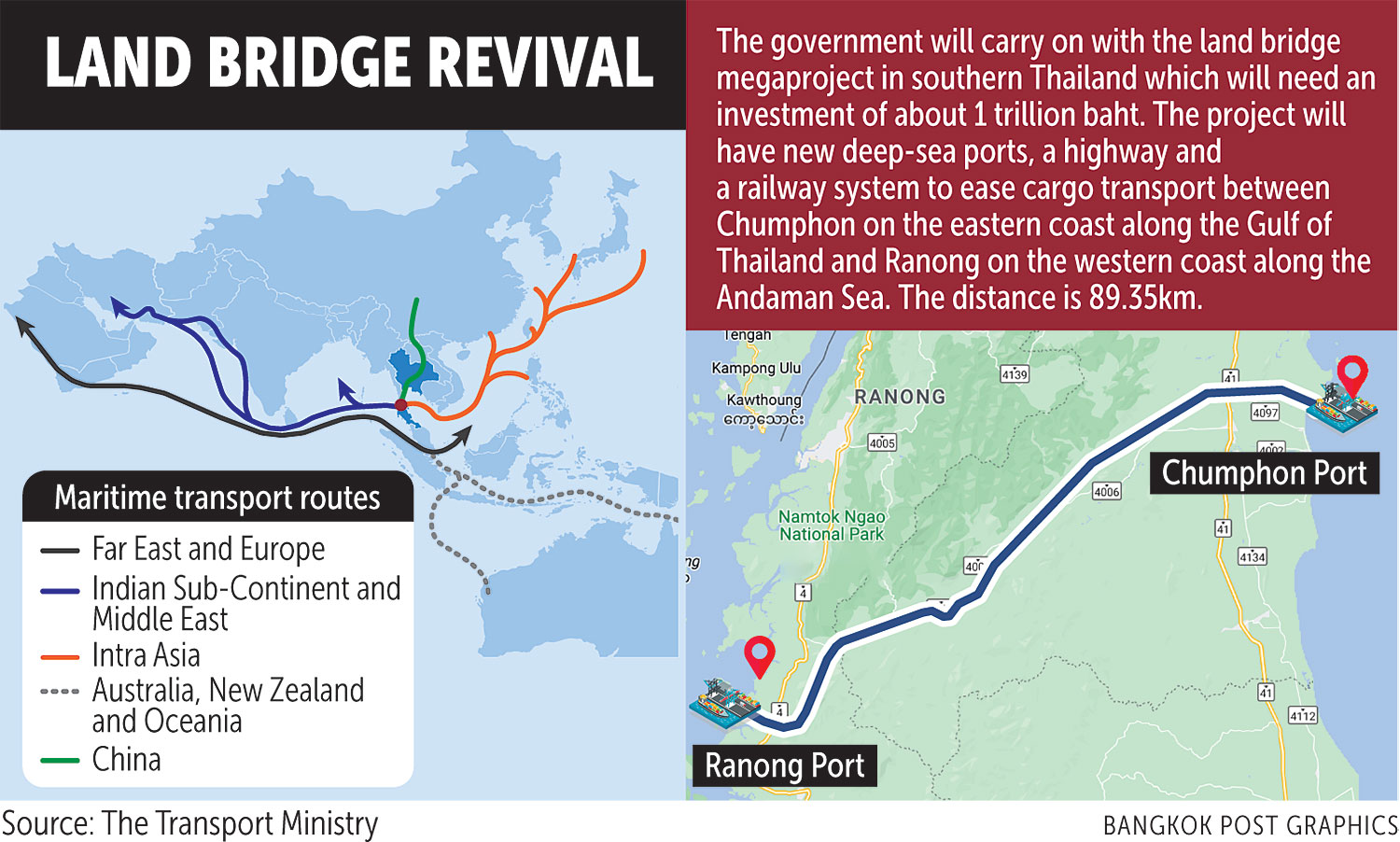

The short video promoting the scheme for the Transport Ministry is even more eye-opening. “A port in Ranong will be developed to be a world-class business centre. A port in Chumphon will become the location of a world-class green, hi-tech industry,” it says.

The die-hard project has come back to life again as the government of Srettha Thavisin has dusted off the scheme and started a campaign to drum up support.

Past governments had been trying to do just what the prime minister is doing now and went nowhere. But the real estate tycoon-turned-politician has promised it will be different this time. “I am determined to make it happen,” he told the Economic Reports Association forum on Oct 25.

The cabinet has already given the green light to an estimated construction cost of at least 1 trillion baht. Where will the money come from? No worries. It will be under the public-private partnership format. The government will take care of land appropriation and a one-metre gauge train track to connect it with the existing southern rail line.

The rest to be carried out by private investors includes a deep-seat port in Muang district of Ranong on the Andaman and another one 90 kilometres apart in Lang Suan district of Chumphon on the Gulf of Thailand; a motorway, gas and oil pipelines and another train line with a wider track exclusively built to transport goods for the project.

“This may be one of the largest megaprojects in the world, which would make Thailand an attractive country for investment,” the prime minister said.

“This may be one of the largest megaprojects in the world, which would make Thailand an attractive country for investment,” the prime minister said.

The government will soon hit the road to sell the project to investors. It dreams of starting construction in 2025 and seeing it operational by 2030.

The government is optimistic investors will buy into this scheme during road shows, thanks to its location and potential. The land bridge project can save time for ships of up to 10 days from using the busy Malacca Straits, and investors will be allowed to operate it for 50 years before handing it over to the state.

Everything about the bridge to connect the two waters looks rosy, at least on paper and in PR stunts. But it might be different in reality. And last year’s pre-feasibility study by Chulalongkorn University (CU), commissioned by the National Economic and Development Council, has already pointed out some issues on the other side of the story.

Saving time by using this shortcut is not the only issue that all ships factor in as they have to calculate the double-handling cost of containers loaded from one ship to another waiting on the other side of the coast, the study says. The land bridge project would be attractive only for main vessels to unload freight to feeders, while ships sailing non-stop between the two seas will be not interested in using the Thai bridge, it adds.

And do not forget the two southern provinces where the land bridge is situated have a valuable price to pay. Tourism in Ranong would be in danger, especially when the country is considering proposing Mu Ko Ranong National Park and Laemson Marine National Park as World Heritage sites in the long run as the land bridge and port stand on the buffer zone within three kilometres of the parks.

Lang Suan district in Chumphon is not on the main tourist map but it is one of the fruit bowls in the southern regions famous for rambutan and mangosteen. In addition, coastal fishing communities and farmers will have to make way for the new infrastructure to be built on the two coasts and inland.

At least what is recommended in the CU study is worth considering. It suggests infrastructure which is already there in the South, from the railroad to roads and ports, be improved rather than going ahead with this megaproject.

The project began in 1993 when Chuan Leekpai was the prime minister, to link Krabi and Nakhon Si Thammarat. Thailand even convinced Malaysia in 1994 to join the scheme to rival the Singapore port by linking the ports in Penang and Songkhla. More sites have been mooted since then, including Satun and Songkhla. Every time the plan is raised, it always ends up back on the shelf with no one interested in putting up the huge sums needed.

History loves to repeat itself, and this land bridge project is no exception.

Source: https://www.bangkokpost.com/opinion/opinion/2678883