I tried to build a life in Thailand as a foreigner — here’s how the system pushed me out

I tried to build a life in Thailand as a foreigner — here’s how the system pushed me out

Justin Brown

ED: Interesting article which I think will resonate with most of us who have lived in Thailand for some time.

This is an update of the article we published in April 2025.

Justin Brown, an Australian entrepreneur, tried to settle in Thailand, but faced obstacles and ended up leaving the country.

Here is his testimony:

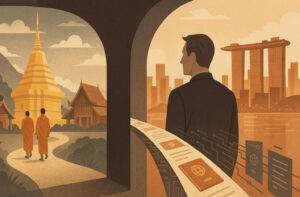

The first time I landed in Bangkok , the air hit me like a hot, humid embrace, laden with diesel, jasmine, and the sizzle of streetside pad kra pao

I was then a solitary traveler, wide-eyed and restless, chasing the raw pulse of a place that seemed worlds away from the sterile grids of my past.

Thailand immediately captivated me: the golden spires piercing the horizon, the saffron-robed monks gliding into the dawn, the chaos of tuk-tuks winding through the alleys.

From tourist to entrepreneur: a new beginning in Chiang Mai

Years later, I returned, not as a tourist, but as someone ready to build a life for myself.

I was running a quietly thriving digital media company, and I saw Thailand as a place where I could combine ambition with a slower, richer existence.

Chiang Mai seduced me with its misty mountains and old-town charm, a place where I could work at a teak desk and dream of permaculture plots in the hills.

I arrived with a work visa in hand, a two-year ticket to explore this vision, and a heart full of respect for a country I had come to love.

But as the months went by, I learned something profound: the Thai system, which I deeply admire, was not meant for me to stay.

It’s a system that preserves something rare and vital, a cultural fortress in a globalized world, and while it pushed me to leave, it also led me to Singapore, where I was able to pursue the integration and fulfillment I needed.

My first days in Chiang Mai were electrifying. I settled into a rented house near the Ping River, its wooden floors creaking under my feet, its windows framing views of the forested slopes of Doi Suthep.

I had obtained my work visa through my company, a small but growing business that allowed me to work legally, without having to cross the border, and I started life here.

Mornings began with the clatter of noodle carts and the hum of chanting monks; afternoons turned into Thai lessons, where I struggled with the tones until my teacher’s nods became signs of approval.

I wasn’t naive, I knew Thailand had rules, boundaries for foreigners like me, but I thought patience and effort could bridge the gap.

I wasn’t there to demand or complain; I wanted to contribute, to integrate into this mosaic of places.

And for a while, it seemed possible.

I sipped coffee with local artists in Nimmanhaemin, swapped stories with vendors at the Sunday market, and hiked near Pai where the air tasted of pine and possibility.

But slowly, subtly, the system revealed itself, not as a wall to climb, but as a riverbed guiding me elsewhere.

The visa system, the first obstacle

Thailand’s visa policies were my first lesson in this gentle reorientation.

I arrived with this work visa, linked to my company, which allowed me to settle for two years.

It wasn’t the flimsy tourist visa I’d used on previous trips, nor the student visa I’d once considered, learning Thai to extend my stay.

It was a legitimate pass, proof that I was there to work and build.

But as the two years went by, I began to look ahead: Could I make this situation permanent?

The options were clear.

The Elite visa for Thailand loomed on the horizon: 500,000 baht (about $15,000) for five years, renewable for up to 20 years with enough money.

It looked promising until I dug deeper.

The Elite is a luxury tourist visa, not a means to obtain residency.

It offered me no right to work beyond my current status, nor any anchor for a more stable life.

Permanent residency, the Holy Grail, was a mirage: decades of residency, a clean record, fluency in Thai, and a series of approvals that few foreigners manage to obtain.

In 2022, Thailand granted permanent residency to only 117 applicants out of a population of 71 million, a needle’s eye I couldn’t get through.

Even my renewable work visa felt like a reprieve, tied to my company’s performance and the whims of immigration officials.

Historically, this makes sense.

Thailand’s visa system tightened after World War II, when the country became one of the few in Southeast Asia never to have been colonized.

While neighbors like Malaysia and Vietnam bore the scars of British and French rule, Thailand skillfully played the diplomatic card, balancing Western powers to remain sovereign.

This independence has bred fierce protectiveness, a desire to control who stays and who leaves.

Post-war immigration laws, refined in the 1970s with Immigration Act BE 2522, set strict quotas and conditions, prioritizing Thai jobs and security over foreign settlers.

Today, with tourism accounting for 12% of GDP ($54 billion in 2019 before the pandemic), Thailand welcomes millions of tourists each year, but keeps the door ajar, not wide open.

The system filters long-term integration, preserving the economic control of its people.

I respect that.

It’s a shield against the cultural dilution that has swept through places like Bali, where foreign money has transformed villages into Instagram backdrops.

But for me, it meant there was no clear path to permanence, no way to plant roots beyond the next renewal.

A dream of land… shattered by the law

Land ownership was the next thread in this complex web.

I had always had this vision, perhaps naive, perhaps romantic, of a small plot where I could build a house and experiment with permaculture.

The outskirts of Chiang Mai seduced me with their patchwork fields, the hills of Pai made me dream of quiet retreats, and even the rugged plains of Isaan caught my eye during a motorbike tour.

But Thai law stopped me in my tracks: foreigners cannot own land outright.

It’s not an oddity, it’s a cornerstone.

The 1954 Land Code cemented this, banning foreign ownership to protect Thai farmers and thwart speculators, a legacy of resistance to colonial land grabs that dispossessed other nations.

There are workarounds: a 30-year lease, renewable if luck is on your side; a Thai spouse holding the title deed, love or luck; a corporate structure, 51% Thai-owned, with piles of paperwork and legal fees.

I’ve explored them all.

I met agents in Chiang Mai who outlined deals over lukewarm Singha, lawyers in Bangkok who offered five-figure fees, farmers near Mae Rim who shrugged at my questions.

One afternoon in Pai, I stood on a hillside plot, rice paddies below, mist rolling in, and asked the owner for a lease.

“Thirty years,” he said, “but after that, it’s mine again.”

I nodded, smiled, and left.

The risk was too high, the control too fleeting.

This isn’t petty stubbornness, it’s strategy.

Thailand’s 513,120 square kilometers are 70% agricultural, feeding its population and economy.

Letting foreigners buy land could drive up prices, push out locals and echo the land rushes that plagued postcolonial states.

As of 2021, foreigners owned less than 1% of Thailand’s land through indirect means, a stark contrast to Vietnam, where foreign investment has engulfed coastal strips.

The Thai system keeps its soil in the hands of Thais, a bulwark against the upheaval of globalization.

I love it.

It’s a refusal to sell out, a middle finger to the idea that everything is for sale.

But it left me a perpetual tenant, my permaculture dreams deferred, my sense of place disconnected.

Limited cultural integration despite efforts

Then there was the cultural current, more subtle, but just as strong.

Thailand’s warmth is real, smiles at every turn, kindness in every bowl of khao soi , but its social fabric is a tapestry that outsiders rarely weave.

I worked hard to fit in.

I studied Thai until I could joke with market vendors, I volunteered at temples during Visakha Bucha , I participated with abandon in Songkran water fights .

In Isaan, I spent a weekend with a shaman, drenched in sweat and awed as I learned rituals I will never forget.

But the deeper I delved into my relationships, the more I felt the boundary, not hostility, but a silent reserve.

Friendships remained superficial, invitations limited to polite nods.

At one Loy Krathong , I floated my krathong with a local family, their laughter echoing as lanterns lit the sky, but by the end of the night, I was still the farang, welcomed but not included.

It’s not exclusion, it’s preservation.

Thai culture, forged over centuries by Theravada Buddhism and royal tradition, is not a tourist accessory; it is a living identity, fiercely preserved.

I admire this strength, this refusal to dilute oneself for foreigners.

But it left me on the sidelines, yearning for a community I couldn’t fully embrace.

For readers who have felt victimized by this, those who are outraged by double prices (300 baht for me at Doi Inthanon, 50 for locals) or visa refusals, it is easy to see Thailand as unfair.

I understand.

I felt that pain too, in the beginning, when each “no” was piling up.

But in experiencing this, I saw something bigger.

Dual pricing isn’t just about money; it’s a nod to economic fairness, allowing Thais to enjoy their heritage while tourism foots the bill.

In 2019, 39 million visitors flocked, without these bonuses, residents could be excluded from their own parks.

The maze of visas and land laws?

It’s not personal, it’s systemic, rooted in a history of evading colonial clutches and modern urban sprawl.

Thailand has been open for centuries as a trading hub, with the ruins of Ayutthaya whispering of Persian and Portuguese traders, but it has never bowed to foreign rule.

Today, it is open to tourists (1.5 million Americans in 2019 alone), but not to settlers.

It’s not a flaw, it’s a triumph.

It has preserved a culture where monks still bless rice paddies, where festivals like Phi Ta Khon vibrate with spontaneous life, where globalization has not flattened the soul.

I didn’t struggle in Thailand: my business continued to run, a steady engine of projects and clients, without any visas to obtain.

But I couldn’t develop it there.

Thai work permits beyond my work visa were a unicorn, foreign income was tightly controlled.

Singapore, the possible alternative

Singapore, where my company was already based, beckoned: a hub that embraced my ambition, offered residency-linked entrepreneurship, and allowed me to integrate in a way Thailand couldn’t.

I spent nights weighing the pros and cons: Thailand’s beauty, its integrity, its silent rejection of me versus Singapore’s elegant efficiency, its open arms.

A few years ago, I made the decision.

I packed my bags, taking my life in Chiang Mai with me (teak furniture, Thai dictionaries, souvenirs of mango sticky rice from a Warorot stall) and boarded a plane.

A lucid departure, without bitterness

Neither bitter nor broken, but lucid.

The Thai system didn’t let me down; it succeeded for itself.

I deeply respect this, which is why I will always return as a visitor, soaking up what it offers without asking for more.

My departure was bittersweet.

My last night, I sat on a rooftop in Chiang Mai, the city’s golden chedis glittering below, the air thick with frangipani and goodbyes.

Thailand has given me gifts: resilience, wonder, a lens into a world that doesn’t bend.

I don’t blame him for pushing me, it allowed me to find my place.

Singapore welcomed me, my business, my desire for community, a place where I could build without fighting a system designed to hold me back.

But, Thailand remains with me, a lesson in respect for reality.

His system is not unfair, it is deliberate, the guardian of something special.

For foreigners dreaming of a life abroad, here is the common thread:

Thailand opens its heart to travelers, but not its soil, not its soul.

This is his strength, not his weakness.

I tried to build a life there, I loved it for who it was, and I left, not because it rejected me, but because I needed more.

As the plane took off, the lights of Bangkok fading below, I smiled.

A chapter has closed, a truth has been accepted: sometimes loving a place means letting it go.

[Seen this article by Justin Browne in various places on the internet. Hopefully Justin is ok with us carrying his article]

Source: https://toutelathailande.fr/en/why-did-an-australian-expat-leave-thailand-he-loved-it-so-much./