Chiang Mai power project plans to use waste from processed corn

A Mae Chaem energy project aims to reduce haze and raise farmers’ income

11 November 2019

Mae Chaem district in Chiang Mai has been chosen to kick off the government’s Energy for All scheme for community-owned power projects from renewable resources.

The power project plans to use waste from processed corn.

Agricultural refuse is usually disposed of by burning in an open area, but this has caused a miasma of smog and dust that has reached epidemic levels the last two years.

With Thailand facing emissions from many sources, including road transport, burning refuse has caused dust pollution to increase exponentially.

The community-owned power projects using crop waste are expected to help mitigate the problem.

The first project in Mae Chaem was introduced by locals in late October. The district has been the country’s corn plantation hub for more than 20 years.

Mae Chaem is a peaceful town, similar to other farming communities in upcountry provinces.

The state-run Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand (Egat) has taken an interest in the matter, but it has found many problems being swept under the carpet.

Patana Sangsriroujana, Egat’s deputy governor for strategy, said corn plantations will produce a good return for farmers for the first couple of years, but the farms will suffer a loss because of the monoculture method that depends heavily on chemical fertiliser and pesticides.

The Bank for Agriculture and Agricultural Cooperatives reported that corn farmers in Mae Chaem have incurred combined losses of 2.4 billion baht from monoculture farming.

An Egat study found that because the district is located on a high hill upstream from the Ping River, soil erosion and sediment have slid downward 272 kilometres to Bhumibol Dam, the largest hydroelectric power plant and irrigation area.

The dam suffers from these problems in the water reservoir, stemming from monoculture farming.

“Some 50 years ago, Egat estimated that the Bhumibol Dam would take roughly 400-600 years before it is decommissioned, but recent research found that the life of dam has been shortened from corn farming in Mae Chaem during the last two decades,” Mr Patana said.

After finding severe impacts and seeking solutions to move away from monoculture farming over the past two years, Egat has approached local communities to shift to integrated farming using the late King Bhumibol’s sustainable development principles.

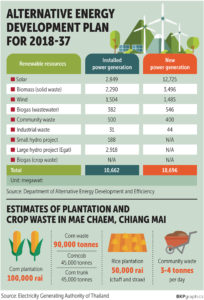

According to data from local administrations, the corn plantation areas cover a total of 170,000 rai and corn waste stands at 90,000 tonnes per year.

Half the waste is reprocessed as fertiliser, wood pellets and animal feed, and the other half is burned in the open.

Together with other burnt crops such as rice and cassava, the dust and smog pollution in Chiang Mai has become more hazardous every year.

Mr Patana said Egat has selected two locations for the first-phase development of community-owned power projects with a capacity of 1 megawatt each.

“Egat is working with a network of social enterprises to build an embankment across Mae Chaem district to be the water reservoir,” he said. “The two power plants will cost roughly 120 million baht each, and Egat expects to show success in management and operation in order to encourage locals to participate in the Energy for All scheme.”

Higher household income

Energy Minister Sontirat Sontijirawong said the government aims to turn crop waste into extra revenue for farmers.

The pilot projects under the Energy for All scheme will involve self-power generation in provincial areas.

“Roughly 70 villages in Mae Chaem district cannot access the electricity system,” he said. “The technology of power plants will be synthetic gas because it requires less raw water during the operation, so each remote area can run self-power generation.”

Mr Sontirat said the ministry is designing and setting up conditions for state agencies, private investors and local communities to participate in the programme.

The budget for each power project comes from the Energy Conservation Fund and the National Village and Urban Community Fund.

Agricultural cooperatives in Chiang Mai’s Mae Chaem district will support the Energy for All scheme.

Mr Sontirat said the first group of power projects under the scheme will begin operation by 2022 with power generation of 400-500MW.

“The ministry plans to seek another three or four projects to participate in the programme,” he said.

The Energy Ministry expects to conclude the business model and details of the Energy for All scheme by the middle of this month.

End of crop monoculture

Monoculture farming will be abandoned to cut crop waste. The Energy Ministry will support locals in growing other plants such as giant acacia and bamboo to serve as biomass fuel for the community-owned power projects.

Uthid Sombat, a farmer in Mae Chaem, said he welcomes the idea of turning crop waste into power for extra revenue for his household.

But he is concerned about the long-term sustainability of operating the power projects.

“Efficient management is crucial because the power plants require technicians and a business mindset to operate them in the long run,” Mr Uthid said. “A sufficient and stable supply of feedstock is also critical, so the government should plan this with great care.”

He said many projects that ran in cooperation with social enterprises only worked for a couple of years, then ceased to be functional and caused a huge financial burden for locals.

Source: https://www.bangkokpost.com/business/1791774/earning-their-corn