Bangkok Metropolitan Administration hopes to build a satellite city to relieve pressure on Bangkok

The centre will not hold

Bangkok Post Special Report

City Hall under the stewardship of governor Chadchart Sittipunt is looking to build a satellite town to “de-urbanise” Bangkok.

However, the plan raises the tricky question of whether the satellite town will eventually grow into a populated, urbanised area, which defeats its purpose of relieving congestion in Bangkok’s city centre.

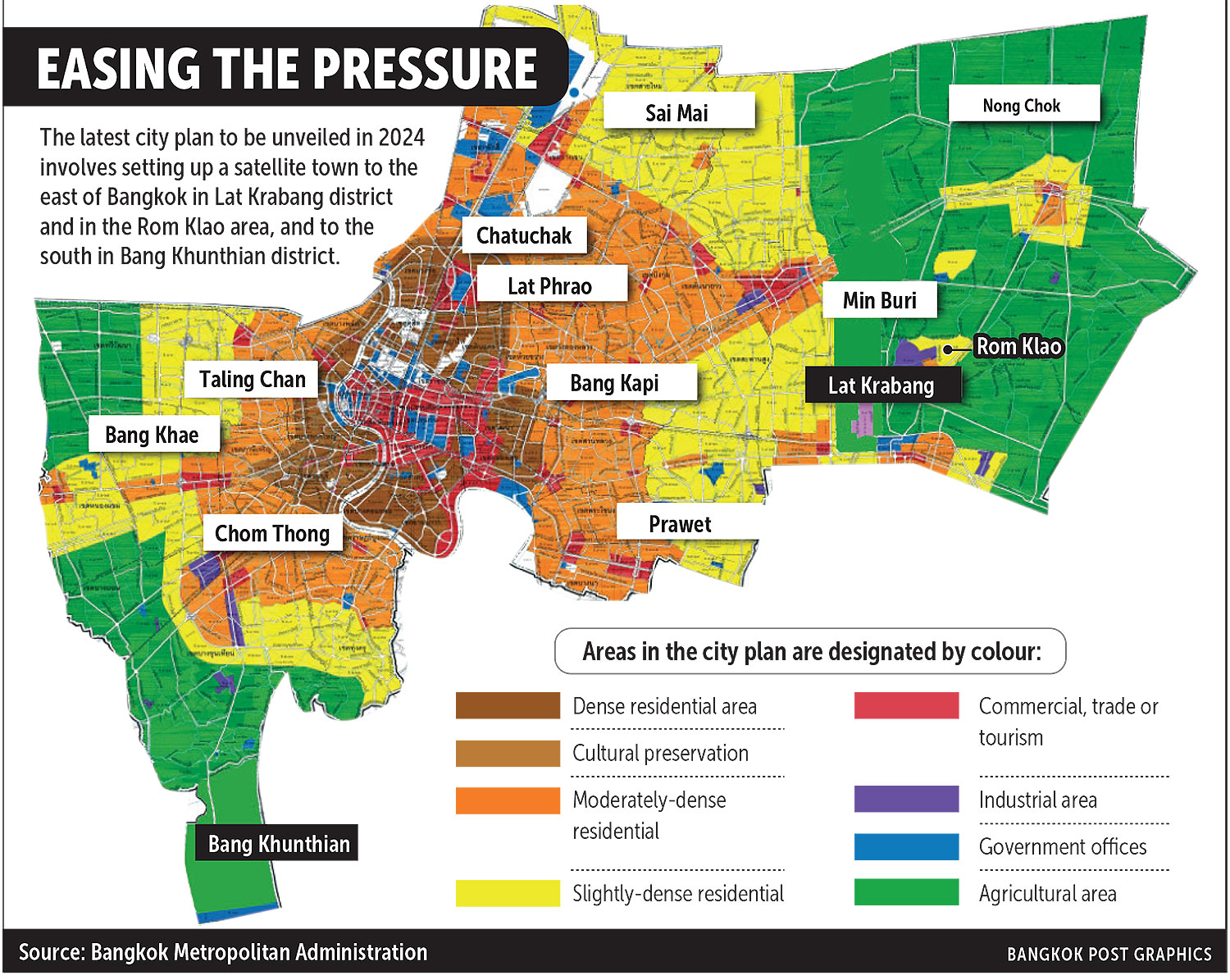

The plan has been prioritised by the Bangkok governor who is eyeing eastern zones encompassing Lat Krabang and Rom Klao, and the southern district of Bang Khunthian as potential satellite clusters.

The satellite town idea dominated the agenda of a recent meeting chaired by Mr Chadchart at the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA)’s Department of City Planning and Urban Development (DCPUD).

The governor envisions a new Bangkok where its development spreads to the periphery more in the direction of Lat Krabang, Rom Klao and Bang Khunthian.

“We need to build an ideal city that will come to life through a plan designed to make it self-contained. This will lessen commuting to the city centre. But it won’t be easy,” Mr Chadchart said.

Satellite town

The satellite town project could be piloted on a large tract of state land owned by such agencies as the National Housing Authority (NHA). The agency possesses hundreds of rai of vacant land.

But the project is doomed to failure if the satellite town has only residents with no office, schools, public parks, mass transit system or hospitals, or not enough of them, the governor said.

The DCPUD will take the lead in working on a self-contained city plan to be reflected in a new integrated blueprint for Bangkok, set for implementation in two years.

Central to a revamped Bangkok is urban development being pushed away from the centre to the suburbs. Apart from tackling overcrowding, it would also alleviate flooding and traffic congestion while setting aside more land for green space.

Rampant heavy floods crippled much of Lat Krabang district this month, which put Mr Chadchart in trouble.

The integrated blueprint is in the middle of drafting which began in 2020. It covers areas adjacent to the Nonthaburi and Pathum Thani to the north of Bangkok, to Chachoengsao to the east, Samut Prakan and the Gulf of Thailand coast to the south, as well as Samut Sakhon and Nakhon Pathom to the west.

Bangkok’s city plan has been through three prior, significant modifications in 1992, 1999 and 2013. The latest revamp was in order as the capital’s physical, socio-economic and demographic environments have changed radically. There have also been changes regarding land use across the city on the back of the new property and building tax which requires owners to pay substantially higher tax for their vacant plots.

The city plan has to be designed more thoroughly, Mr Chadchart said.

The principal problem had to do with the dense population which has reached overcrowding in many areas. At the same time, the state sector has undertaken more infrastructure and mass transit projects such as the electric train routes than planned originally. Large-scale residential and commercial buildings have also sprouted up.

Some 60 city ordinances pertaining to city plan, some dating back 63 years, will be updated, reformed or revoked.

Certain contents of the integrated blueprint earmarked for launch in two years are being reviewed in line with amendments to laws. The blueprint is also subject to a mandatory public hearing before being put into practice.

One area slated for a satellite town is the so-called Thanon Rom Klao land, currently mostly empty, spanning more than 2,000 rai owned by the NHA.

Somchai Dechakorn, director-general of the DCPUD, said that of the 2,000 rai, 650 rai have been developed into housing projects for low-income residents.

However, the area is exclusively residential, so the remaining land will be set aside for building offices, hospitals, schools and department stores to create a self-contained environment. “The NHA is a major landlord and has plenty of land in greater Bangkok to spare that could turn into low-income housing,” he said, citing land in the Rom Klao, Bueng Kum and Ram-intra areas.

City Hall also mulled over the proposed creation of “sub-centres” in outer Min Buri, Bang Khae, Bang Na and Don Muang districts.

Although electric rail routes have cut through some locations in these districts, which have resulted in some rapid realty transformations, they still lack “indispensables” such as schools, hospitals and places that generate jobs, he said.

Sunan Laiwian, head of the Keha Rom Klao Zone 1 community on the Thanon Rom Klao land in Lat Krabang district, said he and his family hail from upcountry and were the first people to settle in the area 30 years ago.

The NHA amassed its expansive land portfolio in Rom Klao from the original owners who had left the land unused and desolate. Some of the land was allocated for resettling people vacated from crowded communities in Klong Toey, Phai Singto and Khlong Chan areas.

While he threw his support behind the governor’s vision to put together a satellite town, Mr Sunan predicted people would commute back to the city centre if schools and hospitals did not follow them to the new town.

More than 100,000 people call the Keha Rom Klao community their home. They live in some 180 tall flats, in addition to at least 30 communities where they bought the land and built their house on it.

“In the beginning, we thought it was enough having a roof over our heads,” Mr Sunan said. “Looking around now we’ve realised what is missing that is crucial for improving the quality of life of our children and grandchildren. They have to brave the traffic commuting back and forth to the city centre.”

Schools are few and far between. Kindergartens are privately-run and out of reach to most families. Some of the nearest universities are a district away.

“Hospitals are also a long way off and the main source of employment is factories. There’s a limited number of public buses in the area,” he said, adding the Orange Line electric train project, which residents thought might swing by their communities, was a daydream.

“We have little choice but head back to the inner city every day.

“If you want to spread out development to the outer zones, you have to ensure quality living as well,” he said.

Not a one-party job

Meanwhile, Panit Pujinda, president of the Thai City Planners Society and associate professor in architecture at Chulalongkorn University, said outward city planning was common in many metropolitan areas.

The Office of Transport and Traffic Policy and Planning has studied the feasibility of building transport hubs in the Phahon Yothin, Makkasan and Wong Wian Yai areas.

But formulating a city plan cannot be achieved by a single party as the scope of authority for some matters was beyond the BMA.

“Quite frankly, if the [satellite town] plan is to have any chance of coming to fruition, it cannot happen without the support of the government,” he said.

Businesses must be encouraged to invest in the town and such incentives come in the form of investment or tax privileges which only the government can issue.

The BMA should also not limit the satellite town project to Bangkok’s borders. It should involve surrounding provinces in the discussion since many Bangkok residents live in neighbouring provinces such as Nonthaburi.

In terms of employment, the Industrial Estate Authority of Thailand should talk to the NHA over how companies may be attracted to set up bases close to a satellite town.

Source: https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/special-reports/2399776/the-centre-will-not-hold